Vanishing Gas Stations: How Traditional Service Stations Have Regressed from Essential Community Businesses to Prime Targets for Redevelopment

As the Washington region grows in population and density, commercial real estate developers have increasingly targeted gas station sites for high-density office and residential projects. This trend has become most prevalent in urban areas inside the Capital Beltway where available land has become especially scarce.

Gas stations are particularly well-suited for redevelopment due to: their relatively large lot sizes (1-1.5 acres for larger stations); typical location on thoroughfares with excellent visibility, easy accessibility, and high traffic counts; and the fact that they are very rarely the highest and best use of the property (particularly in urban areas with high land values). Recent up-zoning to encourage dense mixed-use development in jurisdictions such as Arlington and Montgomery counties have made these sites even more attractive to developers.

On the other side of the equation, the business of owning and operating a gas station has become less lucrative over the last couple of decades. Demand for gasoline has steadily declined as automobiles have become more fuel efficient or run entirely on alternative energy sources. The volatility of oil prices in recent years has also wreaked havoc on the industry, where margins are already razor thin. Contrary to popular belief, gas station profit margins increase when oil prices fall and decrease when they rise. Most major oil companies have sold off their retail gas station assets to strengthen their balance sheets and increase their focus on their core business of extraction, transportation, and refining.

For gas stations with repair shops, regulatory and environmental compliance costs have increased significantly over the years. In order to boost revenues, the industry has been focusing on on-site convenience stores (present at about 80% of all gas stations), although a decline in cigarette sales has been a significant drag on revenue. The most successful chains offer clean, customer-friendly store layouts, dramatically upgraded food offerings, and wide product selections. Mid-Atlantic based chains Wawa, Royal Farms, and Sheetz have especially thrived on this business model, although the land requirements for these gas-store combinations make them far more common in suburban and rural areas than cities.

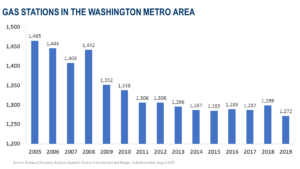

As a result of the industry’s troubles, the population of gas/service stations in the United States has stagnated over the last decade and a half, with the total number of stations increasing just 0.1% from 106,393 in 2005 to 106,515 in 2019 according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The decline has been significantly more acute in dense metropolitan areas with high land values. In the Washington metro area, the total number of gas stations shrunk by 13.2% from 1,465 in 2005 to 1,272 in 2019.

While gas stations continue to be relatively common in the Washington region’s suburbs and exurbs (although abandoned gas stations are becoming more frequent in the region’s fringes) they are now a rarity in the center of the region. While the District of Columbia still has 75 operational gas stations as of 2019—down from 83 in 2004—the vast majority are located along major commuter thoroughfares in the outskirts of the city. For instance, there are no gas stations in the city’s entire Southwest quadrant and only three in Downtown—defined here as a roughly two square mile area bounded by Constitution Ave. NW, 23rd St. NW, P St. NW, and 6th St. NW.

In Arlington County’s Rosslyn-Ballston Corridor—the highest density commercial corridor in Virginia—only four gas stations remain after two in the Ballston neighborhood were redeveloped in the last decade: a Shell where the mixed-use Liberty Center now stands and an Exxon which is now 672 Flats. In Rosslyn, an infamous gas station still operating beneath the Arlington Temple United Methodist Church, will remain (along with the church) even as the larger property is redeveloped by Snell Properties into two residential towers.

It’s worth noting that while urban gas stations remain attractive redevelopment prospects on paper, they are by no means a sure bet, and every potential site should be thoroughly vetted. The most common and costly hurdle is the significant environmental remediation and cleanup work required at most gas station sites.

On top of the environmental issues, the other typical hurdles to redevelopment include community buy-in, the protracted entitlement process, and financing. Until late 2018, the District of Columbia even had an archaic law in place that prevented any full-service gas stations with auto repair shops from converting to any other use without the permission of the Gas Station Advisory Board (GSAB)—a body that had no members since 2008.

Former Georgetown Exxon gas station on M Street NW

Image credit: Google Street View

Perhaps the most notorious example of the difficulty in redeveloping a gas station is the long-planned project at the former site of the Georgetown Exxon gas station at 3607 M St. NW. The property is one of the most prominent development sites of its size in the region, sitting high above the Potomac River near the end of the Key Bridge and Whitehurst Freeway and adjacent to the famous “Exorcist Steps.” EastBanc first proposed development of a five-story, 35-unit condo building on the site in 2011, but since then the plan has been stalled for nearly a decade after enduring one of the most contentious and protracted approval processes in recent memory. The development plan seemed to be universally opposed by nearby homeowners, ANC commissioners, historic preservationists, the Old Georgetown Board, and advocates of a Rosslyn-Georgetown gondola (that want to use the site as the DC terminus). While the site was sold to a new developer in 2016 and the gas station demolished in 2018, there has been no indication that construction will commence any time soon.

As the trend to redevelop urban gas stations continues apace and their numbers dwindle, the strong economics behind redevelopment could theoretically lead to sizable communities losing most or even all their gas stations. While the aforementioned examples of Southwest and Downtown DC show that this is possible, the latter is primarily commercial with far more office workers—who are more likely to buy gas near their homes in the suburbs in the first place—than residents. Downtown also boast a variety of non-auto transportation options. In Southwest, residents need to drive either to Capitol Hill or Crystal City to find the nearest gas station.

In addition to Southwest, there is one urban community in the region’s suburbs with a more balanced commercial/residential mix that has seen its gas stations steadily disappear. We will present a case study on the redevelopment of this community’s gas stations in a future post…